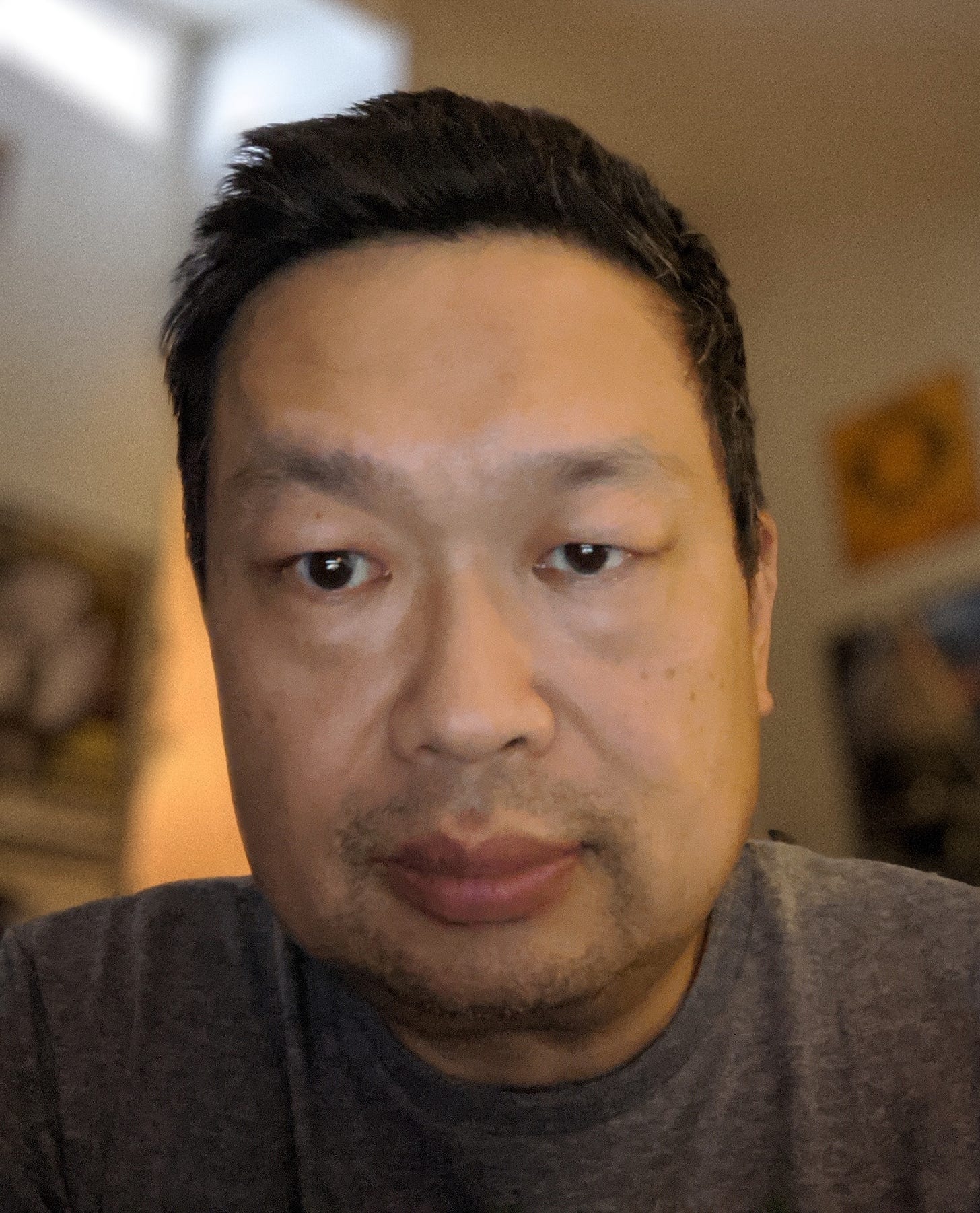

Active Voice #1: Walter Chaw

The Colorado-based film critic discusses writing as an art form, the virtues (and dangers) of Twitter, Film Freak Central, and his love of Roger Ebert.

Writers are a unique breed. We spend countless hours doing something that both drives us nuts and gives our lives meaning. It is both our burden and relief. It’s exacting and exciting. Frustrating and gratifying. We do it because we have to.

Every week, for the last decade or so, I’ve written about films and the people who make them. Reviews, essays, interviews, and film festival coverage. During that time period, I’ve met a lot of my fellow film critics either in person or online, typically through Twitter. We’ve talked shop, made life long bonds, gotten drunk together, resented each other, and sometimes feuded over any number of silly things. But one of the topics that rarely gets discussed is the writing process itself. The craft behind what we are doing day in and day out, and how deeply personal it can become over time.

For this new series entitled Active Voice, I’ll be interviewing some of my favorite film writers about their creative and analytical processes, what inspires them, and how they view the industry at large as it stands today. I hope these conversations will provide a window into the sometimes lonely and maddening journey of being a writer, and the ways in which new experiences, relationships, and tragedies ultimately shape our prose for the better.

Walter Chaw, my first interviewee, is the senior film critic for the award-winning webzine FilmFreakCentral.net. His writing has also appeared in print at The New York Post, LA Weekly, The New York Times, and many other esteemed online publications. Walter is also the author of a forthcoming book on the films of Walter Hill (which I sincerely hope is titled Walter on Walter).

Glenn Heath Jr.: Who was most instrumental in teaching you how to write?

Walter Chaw: I’ve never ever considered that or been asked that question, Glenn [laughs]. I don’t know that I had any kind of physical teacher, in terms of that. I read a lot as a kid. I was a lonesome kid and had a really bad stutter until 6th grade. Bad enough that I really couldn’t communicate. I could get a couple of words out but then I’d stammer. It was a product of real anxiety about speaking English. I didn’t speak English until the 1st grade. I was born in Golden, CO, but my parents didn’t want to teach me English with an accent. So when I went to school, I was surrounded by kids I didn’t understand. Naturally, I thought they were be talking about me, so I’d cry every day. And because I did that they were talking about me. So it was one of those fulfilled prophecies.

And this debilitating insecurity about English led to me having a really bad stutter. The ironic thing now is when I speak Mandarin, my native tongue, I stutter. I’m terribly insecure about my Chinese now. But anyway, because of this I read a lot. The only books we had around in English were ones that my parents picked up at yard sales. So I was reading things way beyond my comprehension, but I was reading them because I was desperate to learn English. I read a lot of Dostoevsky by the time I was 12. I promise I understood none of it. But reading the words and working them through helped. So did listening to records, and transcribing all the lyrics to Simon & Garfunkel songs, and watching a lot of movies. I became a pop-culture savant because it was a lifeline for me, a way for me to assimilate.

In 6th grade, I was asked to deliver a speech to the student body because I had good grades. Obviously it was terrifying. But I wrote it, and the speech received a resounding reception, which was gratifying to me of course. Then a few weeks later, my dad said to me, “Have you noticed you haven’t stuttered at all since the speech?” So it kind of cured my stutter and gave me some confidence in public speaking. I believe my love of writing comes from there. This understanding that writing can be this cathartic and therapeutic outlet. So I’m not sure I had any physical mentors, but I had a lot of ideological and literary ones.

GHJ: When did you first realize that film writing could be an art form?

WC: I initially went to school for engineering, but then quickly transitioned to poetry because of the math. The choices you are given as someone majoring in poetry are, unfortunately, limited. You either teach, or you live in a cardboard box. I’m not smart enough to do the one, and too afraid of hardship to do the other. Film was the one art form that incorporates all of the other arts, so it felt like a natural fit for me. There was actually a period of time, after my Dad had his first heart attack at 52, that I realized I didn’t want to be an entrepreneur or go into business. I went into a period of reflection and contemplation and gravitated toward film criticism. It was another handmaiden to my development, so I was able to translate a lot of the stuff I learned studying poetry, with passion, to the analysis of films.

I always appreciated the great critics and the idea that great critics were also great authors. For me, film criticism is more of a conversational experience with the reader. In my experience, film criticism was never really about the films as much as it was about me trying to communicate with people. At first, it was a really solipsistic exercise since I didn’t anticipate much of my writing to ever be published. I feel like if you go through my work now you get a clear picture of who I was at every point along the way rather than getting a clear picture of the films themselves. And honestly, that was always my goal. It was a process of journaling, unpacking the emotions that were elicited within me in things that I was watching, whether it was love, loss, jealousy, or joy. What are these emotions and what is the root of them and where can I trace them to? All to get a better understanding of myself.

GHJ: How were you introduced to film criticism?

WC: Roger Ebert. I watched At the Movies religiously. I was obsessed and started buying their yearbooks in 1988 or so. I would read them cover to cover, and his reviews and recommendations. They became a sort of gospel for me, and for reasons other than films. A lot of the time I didn’t have the means to track down those movies and watch them. We had some video stores around but they were small. So you couldn’t find something like My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears, 1985). It was genuinely difficult to find those movies. But it didn’t seem to matter so much at the time. I was more interested in the way he was engaging with films. I really heard a human voice in his reviews. I related to it and felt that maybe I could do this as well. I think my first few attempts at film criticism were just blatant ripoffs of styles and tones that Ebert had perfected and trailblazed. I have deviated from there since then obviously, for better or worse. But yeah, it was Ebert who I think gave a lot of my generation of film critics the idea that this could be a career.

GHJ: When and where did you first begin writing film criticism?

WC: Before I ever got published anywhere, I did a Top 100 movie’s list project. I was super depressed at the time. My dad was really sick and I was living in my in-law’s basement. It was just a rough period right after college. So I started making this list, which became an obsessive job for me. It made no money, but it felt productive. I forwarded it to my friends, and it made me happy. I wrote this, I did this.

I first started writing in a public forum for Epinions, this website that was pretty brief. They paid you for clicks reviewing all these products. They had a whole section on film, and for every click, you received a few pennies. It was the dawn of clickbait, the whole internet commerce idea. I met some friends there that I still have to this day. There was a little community of writers and critics and we started talking back and forth over this website. It was social media essentially. We talked about the reviews we had written. I wrote a withering review of Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) and it got a lot of hate and love. And it established for me, that if I could be really funny when I’m really angry then maybe that’s my persona.

For awhile I was looking for movies I could be mean to. I was an early troll perhaps, which I regret terribly. The site eventually went under. But it was there that I met Bill Chambers, the editor, and founder of the film site that I write for now and have for 20+ years, Film Freak Central. He asked me, to work for him. So then began my full-time beat. I’ve done hundreds of reviews since with Bill’s help. He’s a remarkable editor and friend. There was this real feeling of growth during that time, and Bill really refined my voice. He helped me understand what works and didn’t work. He helped me identify crutches that I used a lot. From that exposure with Bill, I started freelancing at places like the LA Weekly, The New York Post, and it’s been great. But my heart belongs to Film Freak Central. I’m eternally grateful for his support and patience.

GHJ: How would you describe your own writing style?

WC: Wow, I guess I would describe it as solipsistic and insular. I think it’s impenetrable sometimes, and I think Bill would agree. It’s hard for me to always articulate what I’m thinking. Sometimes it feels like the thoughts go faster than the writing does. It quickly becomes not about the film, and I have to pull myself back out of it. It’s a really fine line between writing about your life all the time and being an insufferable prick. It’s like with recipe bloggers - people just want to learn how to make the casserole and don’t really care about your Moo-Ma from the old country. So how do I balance this real need to express myself, using the writing and film as a catalyst, with doing something that’s legible for others and not so pretentious and impenetrable that it becomes offputting? Because of that, I have a hard time going back and reading my work. I find it to be embarrassing for the most part.

GHJ: The word I would use is intimate. Films become an entry point for you to discuss these ideas that are very personal. And as readers, they become personal to us too. People are obviously making deep connections with your work.

WC: Thanks for saying so. I’ve heard from some people over the years who’ve really encouraged me to keep going. They’ve said things like, “you’ve really helped me through this tough time. You’ve voiced something I’ve been really struggling with.” For me, it’s those moments that I can poke through the fog of my self-loathing. However personal I fear this introspection can be if it helps someone, even one person feels like they don’t have to stare too long into the abyss or feel a little less lonesome, then maybe it was worth it. Writing is very therapeutic, but sometimes it’s hard for me to become introspective about the process of writing because that feels like another layer of solipsism on top of the inward gazing process for me.

GHJ: What are some trends in film writing that you find problematic?

WC: I think we get in real trouble when film criticism becomes consumer reporting. When someone says, here are the features, here’s who I think will like it. That’s not at all useful. A piece of art is an extant object, and what makes the conversation interesting is how subjective you can make it. I think so many people who are not film critics expect a level of objectivity to the opinion, which is strangely off base. It’s an insane request. And we also run into trouble when you have film critics trying to emulate a certain “film critic voice.” Too often critics try to please every audience instead of writing themselves into the piece.

Like with every act of creation you have to be present. Otherwise, you’re just producing products for someone else. It’s pointless, and there’s enough of it. When I get hate mail, and even death threats sometimes, people say “why didn’t you like this?” And I’m like dude, there’s 99% of people who write the way you want them to write. What is it about absolute uniformity that you so desire? That you have to come here and write something terrible to me simply because I didn’t conform. It’s some Invasion of the Body Snatchers shit right there. Film critics, like in every other industry, have to fight against that. We have to say, we’re more than just a consumer reporting guy. I was moved by this film, and I want to tell you why. Whether I was offended by it or overjoyed by it. There’s a personal element to it that I want to excavate. The objective statements are the least interesting part of any film review.

GHJ: How has your relationship with editors, maybe Bill specifically, helped shape your writing through the years?

WC: Bill is really honest. He’s always apologetic because he’s Canadian. But he’s really honest about things that I do that are irritating. He has a really good ear for nonsequiturs, ideas that are begun and not completed. I write as I speak and think it’s really discursive. I’m not really organized all the time. The first couple of drafts especially. So Bill tells me when things don’t match up. He calls me out when my writing is lazy, and when I don’t back up points of analysis. He tells me when I need to be more specific, otherwise, it just sounds like you’re shining somebody on. We all know how that is. He calls me out whenever I seem tired, or whenever I seem not myself. When I’m not actually doing the work.

It’s easy to fall back into platitudes when you’re writing thousands of words every week. At certain moments it feels like you’ve written the same review 20 times because you’ve seen the same kind of movie 20 times. You say, “it’s well constructed.” “It’s beautifully performed.” “It’s a work of great resonance.” None of those statements really mean anything. When I say it’s “meticulously constructed,” he calls bullshit on me. That’s a term paper colloquialism. Cut it out. So that kind of coaching, pushing, and prodding really helps. He’s helped me be more precise in my ideas.

GHJ: How do you think major transitions in life inspire your writing to change? Like becoming a parent?

WC: I think the answer to that is the same as, how does your life change when these things happen to you? As you know, the moment you hear your baby cry for the first time, everything changes. It may happen countless times a day, but it’s a miracle because it’s yours. When I first heard my daughter cry, I suddenly made a lot of promises in my head. The world immediately becomes a more compassionate place. You join a club, and suddenly understand that your parents loved you so much, and you have a lot to apologize for. It changes everything, especially your approach to examining a film.

We were talking about Ebert earlier, and his criticism changed a lot over the years. At the beginning of his career, he was a firebreathing Kaelite, but toward the end when he was terminally ill and going through a lot of hardship, he became so much more compassionate. Movies that he would have ripped apart in the past, suddenly he’s finding humanity in the filmmakers and he’s really considering those things.

For me, it really is a process. I had found a lot of comfort in being wittingly excoriating of movies for so long that it actually took some interaction with filmmakers to change my perspective. These people had read my stuff and were actually injured by it. It became about being a better human being, I may be scoring points writing this way but it comes at the expense of people who are not deserving of that.

During these life-changing events, your writing does change, but only if you’re being honest with yourself. Your writing has to evolve with you if you’re being genuine about the process. I think I’m a lot nicer than I used to be. I still get angry when a movie is openly offensive and obviously racist, obviously misogynist, or damaging socially. I made worst of lists for a few years and those that made it were never the poorly made films. Most were ones that were fairly popular, but they were espousing really ugly stereotypes and trends in our culture. Those are the worst films. I really reserve the bile for those films now.

I just watched the new Jon Stewart movie Irresistible. It’s really bad, but also fascinating. It’s an expression of absolute cynicism from a person who’s really angry and defeated. It’s so smug and deals in this defeatism that is really interesting. So I want to find a way to talk about that. There’s actually a conversation to be had with it. We all should wrestle with our anger, and the film offers a good way to get into that dialogue. I haven’t been so miserable watching a movie in a long time, so I think that’s worth a conversation.

GHJ: Film criticism is a field heavily dominated by white men. How can the industry do a better job of embracing female writers, writers of color, trans writers, and nonbinary writers?

WC: It’s a big question, and I don’t really have answers to big questions like that. I think at the end of the day, maybe the question is the answer. We need to have more diversity, more voices in the room. The problem is systemic rather than specific. White men are the ones doing the hiring. They are hiring white editors, who are hiring the white writers. Even if your editor is a person of color, maybe they are working for white owners. How inoculated are we as people of color that we start to internalize that sort of racism as well? The systemic issue and the nature of bias being invisible make it a really difficult problem to solve.

Even if you were to hire me into the room, the big secret that I don’t keep very well is that I’m really culturally white. I make the joke a lot that I’ve seen all the Police Academy movies voluntarily. So if you hire me, do you really get that much of a different perspective than if you hired a white guy? Maybe somewhat, because white men probably weren’t bullied the same way I was. But I’ve spent most of my life trying to assimilate into white culture. So am I really the proper spokesperson for Asian Americans?

I’ve kind of become that in a few instances recently. I’ve been asked to write for pretty big sized outlets about Bruce Lee’s depiction in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019). But am I really the most qualified person to be talking about that, or am I what all my countrymen back home called me? Banana, yellow on the outside, white on the inside. I’m a non-threatening Asian voice for white editors in a lot of ways. I don’t speak with an Asian accent. I don’t write with an accent. Culturally, I’m very white American in that way. So who can be a spokesperson?

I do know this though. Wonder Woman (Patty Jenkins, 2017) would have been terrible if it had been directed by a man. But it wasn’t, so there’s something ineffable that can’t be translated. Cléo from 5 to 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962) would have been a very different movie had it been directed by Jean-Luc Godard. So there is something to be said to have those voices, faces, and identities in the room, but it’s just really hard for me to nail down how to solve the issue. It’s a big problem though.

GHJ: You have a large following on Twitter and seem to like using it. What are the positives and negatives of the platform in your opinion, especially as they relate to the field of film criticism?

WC: I really like Twitter because it’s the last place for all its obvious faults. Also, I think it’s the last place for minority voices to have any power in this culture. You can have these powerful conversations there. But its greatest strengths are also its greatest weaknesses. There’s a darker side, like with the cancel culture. It’s kind of sobering. Today, Mel Gibson was trending for a while because it was reported that he said something horrific and anti-semitic to Winona Ryder ten years ago. Minutes later Ron Jeremy began trending because he was charged with raping three or four people. Are those things equivalent? Twitter thinks so.

There’s a real danger to diminishing one and elevating the other. Twitter is such a loud squawk box that everything becomes equally outrageous. I think the real benefit for film critics is that you get to interact with your peers and talent in a way without publicists intervening. I’ve met a lot of great filmmakers there because I’ve posted a review and they’ve read it. They reach out to me through DM and we have a conversation. One of the great thrills of my life was talking to Natasha Lyonne about Russian Doll because I loved it so much. And she knows that now, which is gratifying in a very base animal sort of way. For film critics, I think all of us are in some way are starving for attention. Twitter offers some of that for us. I’ve also learned how to better use Twitter over the years to help promote other people’s work, amplify other voices because I have a slightly larger platform. But it’s also a dangerous place, and sooner or later I think I’ll be on the wrong end of that. It’s just a matter of time.

GHJ: How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted your writing habits, your ability to focus, and carry out assignments? It’s been hard for me personally, so I’m curious what your experience has been.

WC: I think like a lot of us thought that this would be a great period of production. Oh my god, how great, I get to stay home all the time and chain myself to this keyboard. It really has been the opposite. I have 30 fires burning right now with different projects. I’ve started and stopped dozens of reviews that are due. I just can’t seem to find the attention span to get through it.

I have all these open documents flashing at me. It’s a struggle. I’m not sure I can emotionally identify what it is, except maybe the whole world is different and it’s just more traumatic to be alive right now and we haven’t had a chance to assimilate yet. As an introvert, I actually greatly miss going out. I miss going to record stores and book stores. I miss those things. Those were things I did as a means of therapy, the things that would soothe me. Now I just have the guilt of flashing cursors. It’s been anti-productive.

GHJ: Ok, a few fun ones. Who are some of your favorite film critics past and present?

WC: Obviously Ebert. I really love Jonathan Rosenbaum to a point. I admire the way Pauline Kael writes about actors, although I don’t think she was a great critic. I think she was a great sociologist. I like James Agee. I love Manny Farber. A lot of these guys, I don’t understand what they are talking about when they are writing about movies though. Robin Wood’s writing about Hitchcock is really excellent. I also really love Ethan Mordden’s book Medium Cool. It was super influential in the way I thought about movies from the 1960s.

I’ll be honest though, I don’t really read very many contemporary film critics. It’s not a value judgment. I just don’t do it. If you’re a chef, you don’t want to cook at home. If I have time to read, I usually don’t want to spend it reading film critics who are writing now. I want to read other stuff.

GHJ: If you could take one genre of films with you to the afterlife, which would it, be?

WC: I think this answer changes a lot. Right now probably Film Noir. I’ve been revisiting a lot of Fritz Lang’s American work. It’s so perverse, strange, and psychologically twisted. Like House by the River (1950). It’s so weird and fucked up, wrong in so many ways. I thought of it a lot while watching Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man (2020). The whole older brother gaslighting the younger brother into committing murder. Fucked up. This body being compared to a cow carcass and resurfacing in this nightmare dreamscape. Really fucked up. Film Noir is kind of a cheat, though, because it’s not so much a genre but a mood. So I would sneak in all sorts of stuff that wouldn’t necessarily be from that classic time period.

—————————————————————————————————————

Where to Read

3 x Walter Chaw

The Invisible Man (Film Freak Central)

Bruce Lee’s depiction in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (Vulture)

Parasite, the Oscars, and Asian American representation (NYT)

—————————————————————————————————————

Receive all future Afterglow newsletters electronically by clicking the subscribe button. This is a free and public post so please forward. Thank you!

Until next time,

GHJ