If Memory Serves

Afterglow turns 1 (with a little help from our friends)

Afterglow turns 1 this week. Yay! The time has NOT flown by.

In early 2020, I launched this newsletter with the intention of challenging myself to be a more thoughtful critic. I didn’t anticipate it would become a journal of sorts reflecting one of the most emotionally draining time periods in my life. I’m sure it won’t be the last time writing saves me.

Of course, Afterglow’s anniversary coincides with another far more somber one: America’s initial lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Which got me thinking about the overlap between film viewing, experience, trauma and memory. To help commemorate this moment, I asked some of my favorite writers to pick the films they think of when it comes to themes of time, memory, and reflection. No doubt, their words are influenced by the past year’s events. But each response also echoes a sense of hope that looking back through the lens of cinema can help us cope with whatever’s yet to come.

Fernando Croce on El Sur (1983)

It’s odd, writing about remembering when this past year has by and large made me want to forget. Nevertheless, revisiting one of my favorite films about memory, Victor Erice’s exquisitely tender El Sur, was a much-needed pleasure during the early days of the pandemic. I first saw it some ten years ago, in a faded, unsubtitled library copy. To catch up with it in restored Blu-ray form was to watch it anew, a vision of childhood as shifting emotional spaces and indelible sensory moments—the whiff of spearmint or the sweep of a paso doble. A film about enchantment and, in its view of familial and cinematic idols, the need to question that enchantment.

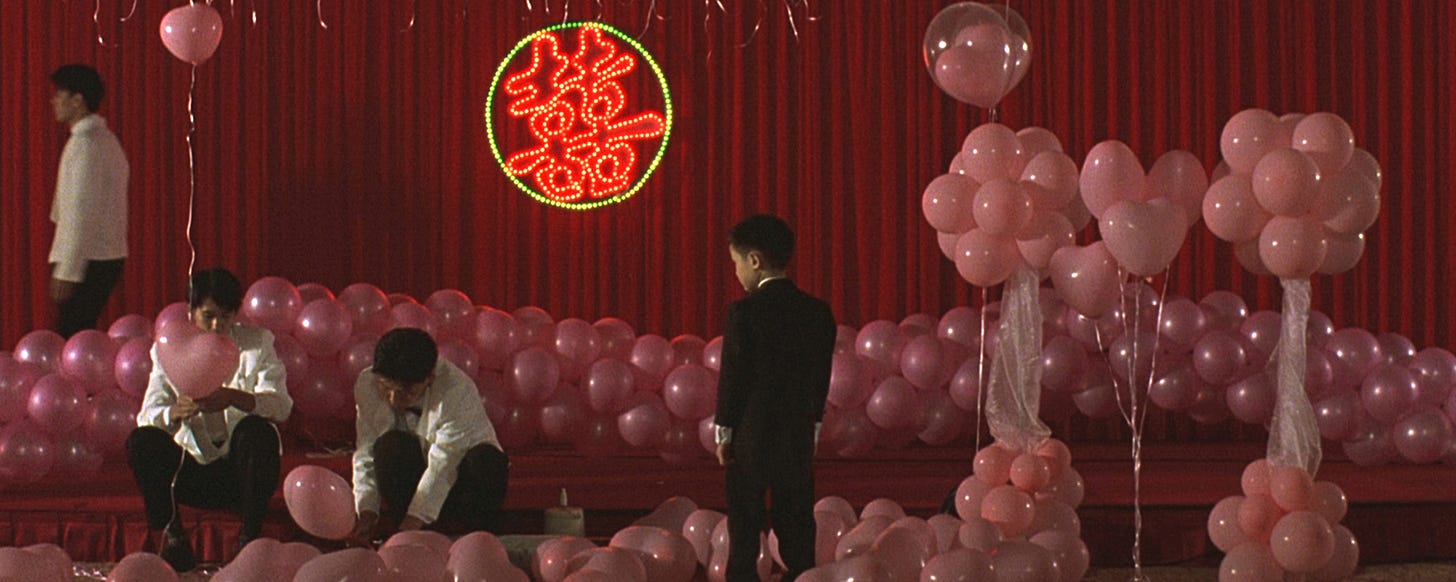

Sean Gilman on The Time to Live, The Time to Die (1985)

In thinking about your question, I keep coming back to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Time to Live, The Time to Die, his 1985 film about his own youth growing up as a transplant from the Mainland in rural Taiwan. Being autobiographical, it’s also a film about looking back at one’s own life, at all the mistakes and failures and missed opportunities and regrets. Hou films everything at a distance, both literally and emotionally, the better to see everything with as much context and clarity as possible. He can’t change the past, but at least he look at it fairly and without judgement. It’s a lesson this year as only reinforced for me: like the past, so much in our world is out of our control. We do the best we can and hope to see more clearly in the future.

Justin Chang on The Tree of Life (2011)

There may be more profound, less heralded movies about memory and recollection — Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A Time to Live and A Time to Die, Peter Segal’s 50 First Dates — but Glenn’s prompt emphasized personal connection and if I’m honest, this is the one that cuts deepest for me. I first saw The Tree of Life several days before its Cannes premiere — and several days after my father’s death. Work was a huge source of comfort during those sad, terrible days and I remember driving to the 20th Century Fox lot that afternoon not out of a sense of duty, but with relief and gratitude for the distraction. I was expecting the movie to be beautiful and contemplative; I wasn’t expecting a portrait of childhood so precise, so attentive to the contours of a boy’s relationship with his father, that it left me feeling both devastated and oddly consoled, as if the movie had opened a wound and applied a salve in the same stroke. My dad was not that dad on the screen, and not just because he didn’t much resemble Brad Pitt; he was a tender, affectionate man and not a particularly strict disciplinarian. Terrence Malick’s memories are not my memories, to say the least. But emotional recognition goes beyond surface similarities. Malick goes so deep into his own spirit that he somehow brushed up, in ways I still don’t fully understand and never tire of thinking about, against mine.

James Jay Edwards on The Butterfly Effect (2004)

Looking back on life can be reflective and meditative. But if remembering this last year has taught us anything, it’s that it can also be chaotic. The Butterfly Effect stars Ashton Kutcher as a young man named Evan who experienced blackouts as he was growing up. In an effort to remember his youth, he begins reading through his journals. It works too well – not only does he start remembering his past, he finds that he is able to change it. It’s easy for the audience to see why Evan’s memories have been repressed. His childhood is extremely disturbing, and the film’s treatment of his history is shockingly visceral. Evan may have forgotten the events of his past, but the audience won’t. Although he doesn’t know it at the time, Evan’s blackouts were protecting him, in more ways than one. For many, 2020 was a year to forget. Sure, it’s had its highs and lows like any other year, but for the most part, people want a redo. Just be careful of what you wish for.

Willow Catelyn Maclay on Twin Peaks (1990-2017-???)

“I’ll see you again in 25 years.”

I rewatched the Season 2 finale of Twin Peaks on the evening that it returned to television after twenty-five years in hibernation and was confronted with Laura Palmer whispering from beyond the grave that she would see Dale Cooper again in 25 years. It all felt so unbelievably haunted and then the episodes that aired presented a version of Twin Peaks that seemed to be in a state of complete decay. There was nothing of the old world that remained and when the Chromatics took the stage to perform “Shadow” in a flurrying burst of nostalgia, that too was snuffed out as the series moved on. The narrative of Twin Peaks is circular, where the past repeats itself, is reborn, and then suffers the same fate once more. Time is ambivalent in its violence and its forward momentum. Whatever the future holds for us, we will all be older, we will all be carrying the wounds of the past, and in some cases the ghosts of those we knew will only be reached in realms that are not our own. I took your picture from the frame and though you’re nothing like you seem, your shadow fell like last night’s rain. Brings back memories, man.

Neil Young on American Graffiti (1973)

Ryan Bradford on Deep Red (1975)

When I was a young gorehound, I watched a lot of Giallo movies for their intricate, violent and brightly colored deaths (“giallo red” would a great name for a shade of paint sold at Home Depot, imo), but now I love those films for the strange dream logic on which they rely. In a handful of these movies, characters solve mysteries not through detective work, but exploring their own memories. In Dario Argento’s Deep Red, the main character witnesses a brutal murder, and spends the rest of the movie interrogating his own memory to answer whodunit. Granted, it’s not the best way to engage mystery-fans—why would I be invested if everything relies on the main character just suddenly remembering?—but I think it inadvertently makes a good point about how people deal with trauma and obsession. I’m not sure if Argento was explicitly saying this when he made his film (he also uses this technique in Suspiria) since his films are mostly style/fetishized violence over substance, but I always think of Deep Red when thinking back to past instances that have fucked me up.

Joel Mayward on After Life (1998)

In his massive tome Memory, History, Forgetting, philosopher Paul Ricoeur observes an aporia: that our only real access to the "objective" historical past is through our individual and collective memory, which is inherently subjective and mediated by our imagination. Ricoeur notes that our memories appear as images, eikons that we "see" in our minds and hearts. Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda literalizes this notion of memory-as-moving-image in After Life, a quietly humanistic work of cinematic beauty. In an afterlife way-station, deceased souls choose their happiest memory to define their post-mortem eternity, which is then cinematically recreated by a celestial film crew. Kore-eda grounds the film in magical realism, and the result is both nostalgic and whimsical without ever tipping over into the territory of mawkish sentimentality. We as the audience are invited to consider our own happiest memories, which in turn is a self-reflective exercise about our very identities: our experiences, our relationships, our losses, our triumphs. For me, in this present pandemic era where reality feels like a way-station and any sense of a "normal" or "happy" life can feel like an irretrievable loss, After Life provides a sense of empathy, even comfort. All is not lost because all is not forgotten, both in this life and the next.

Rhonda “Ro” Moore on Blade Runner (1982)

I don't fully know why but Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner (1982) comes to mind first when thinking about stories dealing with memory. It's based on one of the first science fiction short stories by Philip K. Dick I ever read and watching Scott bring it to life immediately hooked me on lo-fi noir and stories revolving around memory, introspection and fear of being betrayed by one's own mind. The aspects of Blade Runner that make it a dynamic chase film also changed how I thought about the value of memory and my own humanity. Watching a man declared not human - in the opening sequence - because it lacked memories of a mother hit me hard. If pressed, I might be able to recall childhood memories around age seven. So, tying memory to identity in such a mesmerizing setting and layered narrative that justifies hunting a being down shaped my expectations for dystopian/cyberpunk narratives. It also made me wonder what my years long blank spot said about me. Yes, I asked my parents if I was an android. The subtly with which Scott uses the women MCs to build a subplot about false memories, exploitation and agency, one that implies that an inability to recall somehow makes you other, lessor; taught me invaluable lessons about the nature of government control. The starkness of the narrative amidst such neon infused confusion reinforced the unreliability of memory and learning who to entrust with remembering (for) you. This dystopian noir captivated me with its murky visuals, exquisite use of silence, and complicated translation of Dick’s work into a slow creeping allegory that reminds me slavery isn't ever just in the mind. I root fervently for the Replicants to truly break free every time.

Brian Hu on Yi Yi (2000)

There are so many things to love about Yi Yi – the orchestration of family members and their unspoken emotional reverberations, a child’s perspective on a city of sadness. But this past year taught me to appreciate that it is also a film of physical solitude. Within Edward Yang’s many boxes – windows, doorways, apartments – are men and women, young and old, taking time for themselves to parse through in exquisite everyday tempos, their own agency under the specter of death. In Yang’s effortless and brilliant crosscutting, past and present become entangled until the harshness of solitude becomes somehow transcendent of time: both mundanely of-the-present and gracefully eternal, both time-less and timeless.

Michael Snydel on Still Life (2006)

I’ve lived in a city for more than a decade now, but that anniversary came and went without much thought. Rather, I’ve started thinking of my time in markers of places that have come and gone - restaurants and theaters, but also bumpy, paved streets that I kind of miss. Jia Zhangke’s Still Life was the last film that really captured that feeling with its story of two people whose daily lives have been defined by overhead construction. Fengjie doesn’t appear to have much in common with Chicago, but it felt right. Other films had the nightlife right, the loneliness of sidewalks, the lights, but few evoked that other feeling of the world always moving and changing around you in stops and starts. I miss those places that are gone, but hopefully there’s something else great there soon.

Scout Tafoya on the cinema of Victor Erice

The answer has got to be the work of Victor Erice, who consciously uses cinema to converse with the parts of our brain where memories are stored. In Spirit of the Beehive, childhood is rendered as a series of unknowable but dreadful losses, reflected in a child’s understanding of a movie. In El Sur, one of the few movies I’d feel confident saying is perfect, his own recollections become caves of sorrow illuminated only by glimmers of happy memories and understanding. In La morte rouge his own memories linger with filmed images from movies he loved. The very foundation of his worldview comes from the free and fantastical mixture of his mind and the things he watched on movie screens. He’s one of the few directors who really and deeply understands what cinema’s most important function is: to replicate the feeling of remembering something, to turn memories into dreams.

Please consider subscribing to Afterglow! Thank you for reading!