Loving so Deeply: An interview with Zeinabu irene Davis

On the history of black independent cinema and the lasting impact of her incredible 1999 indie film COMPENSATION

Click “Subscribe Now” and receive all future Afterglow newsletters free of charge directly to your inbox. Paid subscriptions are also available and help make future newsletters possible. Please feel free to forward this newsletter to friends and family. Thank you for reading!

American film history has long been presented as a story of white voices, perspectives, and faces. Hollywood continues to be especially adroit at convincing the general public and flourishing creative communities that fame, opportunity, financing, and canonical recognition remain contingent on their narrow view of success. Conversely, the collective acceptance of this narrative has left artists and audiences of color underrepresented behind the camera and onscreen respectively since the silent era, normalizing generational patterns of inequality, disenfranchisement, and caricature in the process.

Any worthy historiographical examination will, of course, reveal a more complex and robust reality bursting with pockets of innovation, expression, and resistance to the status quo. Ever since film became a commercial medium, certain Black independent filmmakers have successfully challenged mainstream conventions creating vibrant work about unjust social institutions, hateful governmental policies, and racist violence that have shaped Black experiences specific to their day. I’m thinking about Oscar Micheaux, Spencer Williams, Melvin Van Peebles, Charles Burnett, Spike Lee, Kathleen Collins, Julie Dash, Marlon Riggs, and more recently Barry Jenkins and Terrence Nash to name a few.

But even those directors don’t fully represent the swath of Black independent voices who’ve created essential work over the decades only to face marginalization or erasure by the system. This is why filmmakers like Zeinabu irene Davis are so crucial to telling a more inclusive story of American film history, both as it stands in the past, present, and future tenses. Educated at Brown and UCLA where the spirit of the LA Rebellion filmmakers shaped her philosophy and production mindset, Davis has worked independently of the studios for her entire career, making mostly short and mid-length documentary and fiction films while teaching as a Professor of Communications at UC San Diego.

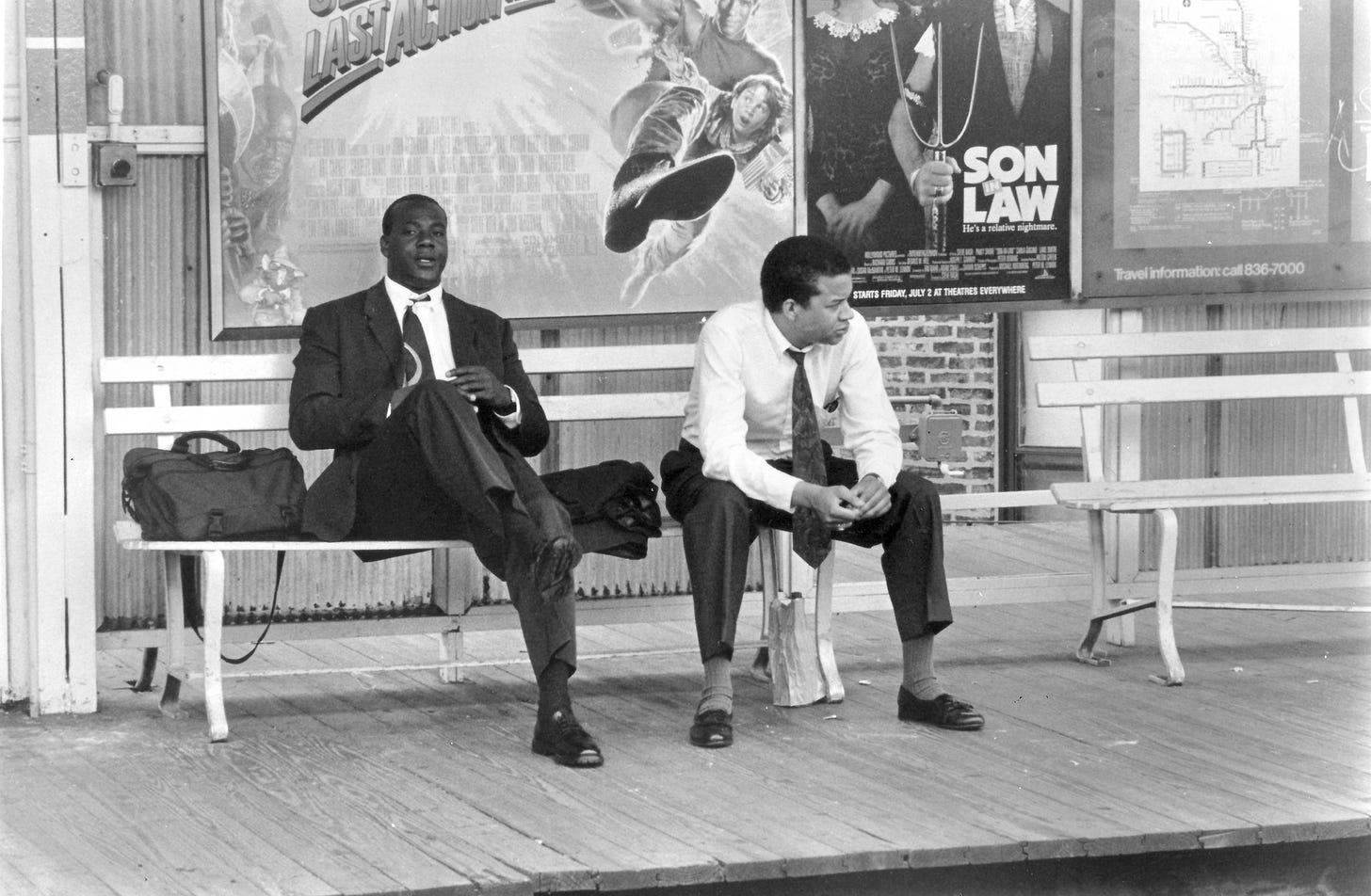

Her lone feature narrative Compensation (1999) takes its title and inspiration from the short melancholic poem by African American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar. In the film, his words drift powerfully through time and space, informing and reverberating through two very different love stories bookending the 20th century. Each couple is played by Michelle A. Banks and John Jelks and incorporates scenarios of miscommunication and epiphany between the deaf and hearing worlds. Additionally, Davis uses archival photographs to help recreate 1906 Chicago as seen through the eyes of its Black citizens. This densely constructed dual narrative - immersed in silent cinema aesthetics, melodrama, tragedy, and love - serves to rewrite the popular record of cinema with more singularity, inclusivity, and nuance.

Compensation is a film unlike any other I’ve seen, and in a way that’s saddening to admit. How many others with similar verve and ambition remain unseen or unmade? Free of all narrative and genre conceits, Davis’ film examines the social and emotional limitations that keep us from embracing happiness completely in times of transition. In that sense, it’s a universal story fueled by disappointment and regret. Still, by charting a timeline of early 20th century black history, experience, culture, and activism, the film begins a beautifully seamless process of recognition and reclamation for the voices, perspectives, and faces of color that have for so long been cast aside, forgotten, or in many cases omitted completely.

I spoke with Zeinabu irene Davis over Zoom about the legacy of Compensation, how her filmmaking and teaching have intertwined over the years, and what lies ahead for future projects.

—————————————————————————————————————-

Glenn Heath Jr.: When did you first fall in love with film?

Zeinabu irene Davis: Oh wow that’s a long story [laughs]. I’ll try to keep it short though. I am originally from Philadelphia, PA, and the daughter of working-class parents. Neither my mother or father was able to finish college. My father started college but endured a lot of racism at Drexel University and consequently dropped out. This wasn’t just something he told me; it was something I was able to have conversations with him about as I got older when he felt more comfortable telling me the truth.

My parents were fans of the arts. They would take me and my brother to whatever events were going on that they could afford, but my father and I would go to the theater or movies. When I was in high school we attended the first Black film festival in Philadelphia. By that time in 1980, we’d had the run of black exploitation films, stuff like Shaft (1971), Superfly (1972), Coffy (1973), and many others subsequently. But I hadn’t seen any black independent cinema up until that point, and it was kind of amazing the impact it had on me. I saw the work of what would then be called the LA Rebellion filmmakers, including Melvonna Ballenger’s Rain (1978) and Ben Caldwell’s I & I: An African Allegory (1979). That put a seed in me that would not come into fruition until a little bit later.

At Brown University in Rhode Island, I planned on becoming an international lawyer because that’s what good working-class parents want their kids to be: either a doctor, lawyer or teacher. Initially, my major was International Law, but I had to take economics and this A student failed it. I took it again and got a C. I knew it wasn’t for me. Later, I got an opportunity to intern at a local television station and worked on a public affairs program called Shades. I learned darkroom photography, how to write scripts, and interview people. We got to interview Bob Marley but also did all kinds of shows about police brutality back in the early 1980s. I really got steeped into the power of media through that.

Finally, the way that I shifted from TV to Film was that I spent my junior year abroad in Nairobi, Kenya. I was studying with a very famous Kenyan writer named Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o at the University of Nairobi. He was prolific, writing all kinds of plays and short stories. The Kenyan government had imprisoned him in the late 1970s for his work. So for him to be teaching at that time in 1980 was a big deal. He had recently been released from prison but the Kenyan government was still watching him. We started production on a play that was about the history of colonization in Kenya.

It was a very community-oriented piece where the actors would perform on one side of the stage and people who fought against the British colonists - the elder Mau Mau freedom fighters - would be on the other side of the stage. My job was to project historical photographs behind them while the play was being performed. Ngũgĩ really instilled in me the power of media and history. Later, the government shut down the university, but that didn’t stop us. We just met up in different places, like cafes and bars around Nairobi. Other filmmakers from primarily Belgium and Germany would visit and we struck up conversations about what they were filming. They were always filming the wildlife of Kenya, never doing anything about the people.

That made an impact on me and my colleagues. As we continued to work on the play, we built a makeshift theater on a soccer field. On the first day of this performance, we had about 1,000 people come. The second day we had 1,500 people. It was growing. On the third day, we couldn’t perform. The government had bulldozed the theater saying the play was seditious. Ngũgĩ had to go into exile. With these experiences, I saw the power to tell stories of underrepresented people and knew that’s what I have to do for a living. When I got back from Kenya, I started looking into film schools and ended up at UCLA, which is how I got introduced to more of the LA Rebellion filmmakers. I told you it was a long story [laughs].

GHJ: The LA Rebellion movement at UCLA began in the late 1960s responding to the rampant social injustice, the Civil Rights movement, and Vietnam War, but its influences spanned well beyond that time period. The collective ethos of their work was passed down from one generation of filmmakers to the next through the 1980s. Is that correct?

ZiD: I would argue it continued long after that well into the 1990s. Scholars and historians say it went from the late 1960s – 1980s, but I would argue it went beyond that, which is the argument I present in my documentary Spirits of Rebellion (2017). It definitely was something that got passed down from group to group. But we weren’t at UCLA calling ourselves the LA Rebellion filmmakers. It was really the historians and scholars that labeled the group once they saw the type of work that was getting made. But I think that the ethos of us working together and with people from our communities, yes that was something that got passed down from group to group.

GHJ: What was it like making films with that kind of spirit while being surrounded by Hollywood, a system founded on a completely different mindset?

ZiD: It kind of depended on who you were and how you felt about filmmaking. For most of us, we really weren’t concerned with what folks in Hollywood were doing, and it didn’t influence us much. Because remember at that time there still aren’t a lot of black filmmakers actually involved in the industry. People kept getting shut out anyways, so we just did our own thing making films that reflected what our concerns were, or what we thought our community’s concerns were. We could experiment because the conventions of Hollywood and western cinema didn’t really apply to us. It was freeing in some ways.

GHJ: You made multiple shorts before Compensation. How did working on short films prepare you for directing a feature?

ZiD: Well, I want to mess with what you just said a little bit. I don’t think I ever thought of it as preparing to do a feature film. Compensation was supposed to be a short film, not a feature. To answer your question more directly, once I started making films I just realized I had to keep making films. It’s like breathing to me, which means I’m not happy unless I’m doing some kind of filmmaking. I don’t have to be on set or in production but if I’m not thinking about making work, or finishing work in the editing room, then there’s a part of me that’s just dead or doesn’t feel right. Making short films was a way for me to keep doing my form. It’s basically a mode of survival and sanity because if I stopped making films I probably wouldn’t be a person. It’s just that ingrained in my psyche. Doing the shorts and different kinds of work, specifically the documentary projects I’ve been doing since arriving at UCSD, it was just a way to keep doing work.

GHJ: Tell me the backstory of how Compensation came about?

ZiD: After finishing school at UCLA I decided to become a university professor. I couldn’t find enough production work and really didn’t like freelancing. Living that industry life was too hard, and I liked teaching. I started at Hollywood High School running a film program for teenagers there, then transitioned to the university level. My first job was at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, which is very close to Dayton, where Paul Laurence Dunbar lived. When you go visit his home, the poem Compensation is on a plaque outside the front door. The poem hit me hard, and I know we wanted to do something with it.

One of the things the LA Rebellion filmmakers do is work with people who are actors and not actors, people who are basically playing themselves. I’m going to borrow this term, they are “social actors.” Borrowing that term from my former professor Bill Nichols, who uses in relation to documentary, but I’m using it because I don’t like saying “non-actors.” While working on another featurette called A Powerful Thang (1991), I gave my lead actor Asma Feyijinmi the poem by Dunbar. She responded to Compensation as a dancer in the NYC dance world where people were dying of AIDS, and that clicked for me and my husband Marc [Arthur Chéry], who writes a lot of the screenplays to my films. Dunbar himself dies of Tuberculosis in 1906 at a very early age, so this idea of connecting a pandemic of the early 20th century with a pandemic of the end of the 20th century was how we could link these two stories together.

Marc and I were visiting St. Paul, Minnesota for an ITVS panel and decided to go out one night after a long day of reading proposals. In the city’s free newspaper we saw a picture of Michelle A. Banks advertising a production of Waiting For Gadot. We went to see her and were totally blown away. I had no experience with deaf folks before. Her performance was so powerful that we did that thing where you stalk the actor afterward and asked her if she might be interested in being in the film. She said yes, and that led us to go back to Chicago and rethink what Compensation could be if it was going to include the deaf community. I started taking American Sign Language (ASL) classes, and we worked with the Black Deaf Advocates Association in Chicago trying to workshop the script with as many deaf community folks as possible and getting feedback.

GHJ: The lead actors (John Jelks and Michelle A. Banks) play two sets of characters from different time periods in Compensation. How did you approach this aspect of dual performance?

ZiD: It was about getting them into the headspace of their characters and creating little bibles. Now you’d call it a “look book” or something of that nature. We tried as much as possible to keep each shooting day set for one particular pair of characters. But sometimes that wasn’t possible, like with the beach scenes. They had to play both sets of characters on the same day because of practical and budgetary reasons.

But my actors are amazing and were always up to the task. Since the end of production on Compensation, they have become my muses. If I could continue to make films with John and Michelle for the rest of my life I’d be one happy camper. They are so generous, they bring a lot of creativity to the role, they respect me as a director, I can ask them to do things I probably could never ask other people to do, but they trust me. They go with it. Sometimes they make suggestions that I take, and sometimes not, but they are always okay with that. It’s a collaboration, not something where I’m dictating from on high. I’ve never run a set like that, and I don’t like working on sets like that.

GHJ: I’d love to talk about Compensation’s core influences – the love story and archival photographs. The former creates a sense of intimacy, whereas the latter creates a sense of immediacy in documenting the black community, experiences, and culture. Can you talk about this juxtaposition and how it framed your filmmaking approach?

ZiD: I love archives. I think they are so important integral to understand our past. We need to honor our past. The fact that there isn’t much representation of African Americans at the beginning of the 20th century is heartbreaking. When I was at film school at UCLA we always watched silent cinema but very rarely saw silent cinema that featured people of color as actors. So for me, really trying to create that world where you could imagine what these people’s lives were like.

I basically had under $100,000 to make this film, and it wasn’t like I could recreate the streets of Chicago in 1905, so I did that with photographs and music. I was super lucky that the preeminent Ragtime composer Reginald R. Robinson happened to live in Chicago. His music set the tone, and again it was that collaborative space. I’m not a musician, but I told him the feeling I was trying to get with the archival film and photographs and with what was happening with the characters. His compositions for those specific scenes really made the thing come to life. I don’t think that would have happened if I was not able to have that good fortune of having that collaboration with other artists.

In regard to the love story, I never thought about it before but that genre does seem to resonate with me. There’s a lack of representation for black couples in romantic love stories, so it was important to me to try and portray these relationships honestly and complexly. Also, to be quite honest, when we do see black people in romantic situations, generally they are very light-skinned. My actors are very dark-skinned, so I think their beauty inscribes the frame just as much as anyone else. It was important for that to come across in the film.

GHJ: I was also struck by the paralleling of silent cinema and talkies with the deaf and hearing worlds.

ZiD: People don’t remember that silent cinema was very much created or designed because of deaf performers. They knew how to project and express with their bodies. I believe it was Lon Chaney, he was the son of deaf-mute parents. And his parents were vaudevillians. A lot of the early Hollywood cinema borrowed from those performers because they knew things that could speak to and express an emotion to an audience without using spoken dialogue. So that was a really important element for me to explore in Compensation.

GHJ: The film’s style is very much indebted to silent cinema, an era that left very little if any space for actors and filmmakers of color. Was Compensation a way for you to reclaim these classic aesthetics by using them to frame the complex experiences of black characters?

ZiD: You hit the nail on the head. It was deliberate. When I was in film school, I had seen films like The Birth of a Nation (1915), so I was definitely using Compensation as a way to subvert the legacy of racism and disenfranchisement in film history, reclaiming as you put it. One specific example is in the period portion of Compensation when the couple goes to the movies. The film they see is based on an actual film made by black folks in Chicago around 1915 called The Railroad Porter. We re-created it. I was able to find a description of the film, in archives of The Chicago Defender. I took the synopsis and Marc rewrote it to be this slapstick comedy and I gave the woman a gun because that’s me. It wasn’t in the original synopsis. Those little things were easter eggs or nuggets for people to know, yes, there was a real film for black audiences with real players and a real black film company. All of it is based on actual facts.

GHJ: Compensation officially premiered in 1999. What was the critical and audience reception like?

ZiD: The only word that comes to mind is bittersweet. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in dramatic competition. Geoffrey Gilmore, the festival director at the time, called it one of the most original films he’d ever seen. Roger Ebert wrote a review for us in the Chicago Sun-Times. We had some positive buzz and people were generally receptive to it, but distributors were not. It was a black-and-white film with actors who were not known. There are probably about 13 minutes before you hear any spoken dialogue. So at that first screening, most of the distributors who did come had already left by that point.

There just wasn’t a place for it in terms of any kind of theatrical distribution. We basically went with an educational model through Women Make Movies in New York. And it’s done well, but I always had that sadness that it was never able to be screened in movie theaters. When you see it with an audience, especially one that is a combination of deaf and hearing folk, it’s magic. I was lucky enough that my department at UCSD decided to do 20th-anniversary screening in October 2019. We did have a mixed audience of deaf and hearing and the response was incredible. I think the most beautiful thing for me, is that even though it didn’t get the recognition I thought the film deserved at the time, we have longevity. This film is 20 years old and still kicking!

GHJ: In our previous correspondence you mentioned another film in the works with Michelle A. Banks. Tell me about what you’ve got planned.

ZiD: After all this time, there is another film in the works. Hopefully, it won’t take 20 years to come to fruition. Being the resourceful independent filmmaker I am, when Michelle was here for the anniversary screenings at UCSD and San Diego Public Library, I asked her if she would be interested in doing these performance pieces that are the beginnings of the new film, which is going to be about three women; Sojourner Truth, who was an abolitionist and suffragette, and an enslaved woman from New York; Phillis Wheatley, a young enslaved writer in Boston and the first black woman to publish a book of poetry in the United States back in 1763; and Marie-Joseph Angélique, who was an enslaved woman born in Portugal that moved to Rhode Island, and was then sold into slavery in Montreal. She was eventually convicted of starting a fire in1734 that burned down much of the city!

My mother is Canadian, so I have a strong interest in Black Canadian history. Unfortunately, most people believe that slavery did not exist in Canada but that’s just not true. It was very different than it was in the US, especially in the South, but it did exist.

So the focus would be on these three women, and I’m planning both a documentary and a video installation intertwining their lives. Right now we’ve done the theatrical performances with Michelle of speeches, poems, and writings from each woman. What I would like to do is have more dramatic reenactments and of course, bring John back to play some type of role in each segment. It wouldn’t be a feature, but a non-fiction piece that would kind of tell us these histories in different ways.

Each woman showed incredible resilience. I want this film to give young black girls an opportunity to learn more about each of them so they can see they are heroines from history and be inspired by them.

GHJ: Ok, now a fun one. As a Professor of Communications at UCSD, what is your favorite film to show students and why?

ZiD: Let me think about that for a moment. [Laughs] Can I say two? The first would be Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). It’s the beginning of cinema history and style. It’s a film I saw in film school and one that continues to rock my world. I love to show students the stairway sequence, and then how it keeps getting referenced in different settings, like Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987) and many music videos. It has this lifespan and trajectory that still connects with students.

The other is Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied (1989), a beautiful personal essay about being a black gay man. Sometimes I get students who don’t want to see it because of strong religious views that don’t allow them to be open to seeing men kissing each other. I ultimately let them make that decision. Some decide to watch it and some don’t, but the ones that do, it shakes them to their core. Marlon was a good friend of mine so I feel an amazing joy knowing that after all these years his work still has such great power.

—————————————————————————————————————

Where to Watch

Compensation will be available for streaming in the near future. If you’d like to receive updates about the film’s future digital premiere, feel free to email Zeinabu directly at zeinabudavis@gmail.com.

Compensation can be purchased on DVD here courtesy of Women Make Movies.

——————————————————————————————————————

Click on the “Subscribe Now” button and receive all future Afterglow newsletters directly to your inbox. Feel free to forward this newsletter to friends and family.

Until next time,

GHJ